How We Could Curb the Youth Sports Arms Race

Like phones, club sports are a collective action problem.

Last week I was chatting with a friend whose daughter had just started playing club soccer. She would have been happy enough playing in a recreational league – the kind run by volunteers where kids play other teams in town – but the rec league in her community had pretty much disappeared, replaced by an array of club teams looking to give kids more intense early training. Her daughter was enjoying it so far, but the coach had told them privately that their daughter was technically behind the rest of the team, and would be a “practice player” for the season, meaning she wouldn’t actually play in any formal games.

Oh, and her daughter is seven.

Soccer is particularly vulnerable prey for the insatiable hunger of the youth sports industrial complex. It’s the evergreen gateway sport for young children because it doesn’t require expensive or specialized equipment, which means kids start early because the barriers to entry are low.

But this also means the stronger athletes join club teams early on, leaving no one behind to populate those lower-stakes local leagues for the kids who didn’t start at age 5. As Tom Farrey, Executive Director of the Aspen Institute’s Sports and Society Program explained, “Soccer is the sport that kids most often play first,” but then “immediately, soccer starts losing them, as travel teams form and community leagues begin to wither, denying a sustained experience from late bloomers and kids whose families can’t afford the youth sports arms race.”

Aspen’s latest data shows that while soccer may be a common entry point, a substantial portion of families commit to an array of other sports at this more intense level, too. In 2024, the Aspen Institute’s Project Play survey found that approximately 38% of kids ages 6-12 participated in a “core team sport” on a regular basis.

Without question, there are many benefits associated with kids’ athletics – like getting exercise, being outside, and learning to be a part of a team. But the push to get kids into more intensive programs at younger and younger ages is a collective action problem that warrants a community-wide response. Without a sense of shared de-escalation, opting out is a hard sell to the parents who worry that their kids will be “behind” (like my friend’s seven-year old) if they don’t get on the athletics escalator while they still have baby teeth.

The opportunity costs of club sports are high, especially for younger kids. Practices crowd out unstructured after-school play and make family dinners impossible. Summer tournaments colonize weekends that could have been spent on family vacations. People claim these leagues are fun, but I have yet to meet a parent who can honestly say they want to spend their free time driving to another state to watch their kid play an endless series of games set against a backdrop of porta-potties.

Ironically, research suggests that there are benefits to waiting to introduce kids into club leagues until they’re a bit older. It’s counterintuitive, but Donna Merkel, now the President of the Board of Directors of the Pediatric Research in Sports Medicine Society, has cautioned: “The earlier a young athlete is identified as having talent, the more uncertain is the prediction of future success.”

This is partly because it’s hard to know how big or strong kids will become as they grow. Kids also acquire physical skills at different rates, and pediatricians advise that many kids in the early or middle childhood years are more appropriately mastering milestones of physical development like balance and posture than highly specialized technical sports skills.

Another unknown is a kid’s long-term motivation, which is impossible to gauge when kids are young. Becoming a standout athlete requires a constant, diligent investment and Merkel warns that kids can easily get burned out by “the endless hours of practice, instruction, and competition necessary to become an elite player.”

I wish I’d recognized this when my own kids were young, when I fretted on the sidelines of rec sports games while other parents talked about how their kids were opting into club leagues. At the time it really did feel like everyone I knew had kids who were specializing in one sport year-round, and I spent way too much time worrying about my kids being left out.

But now that my kids and their friends are almost grown, I can see how Merkel’s claim – that the earlier a child shows athletic promise, the harder it is to predict their future performance – absolutely rings true in my own experience. Many of the kids we knew who were standout athletes when they were 8 or 9 got burned out after a year or two playing club, and ultimately switched to a different sport (or left athletics altogether).

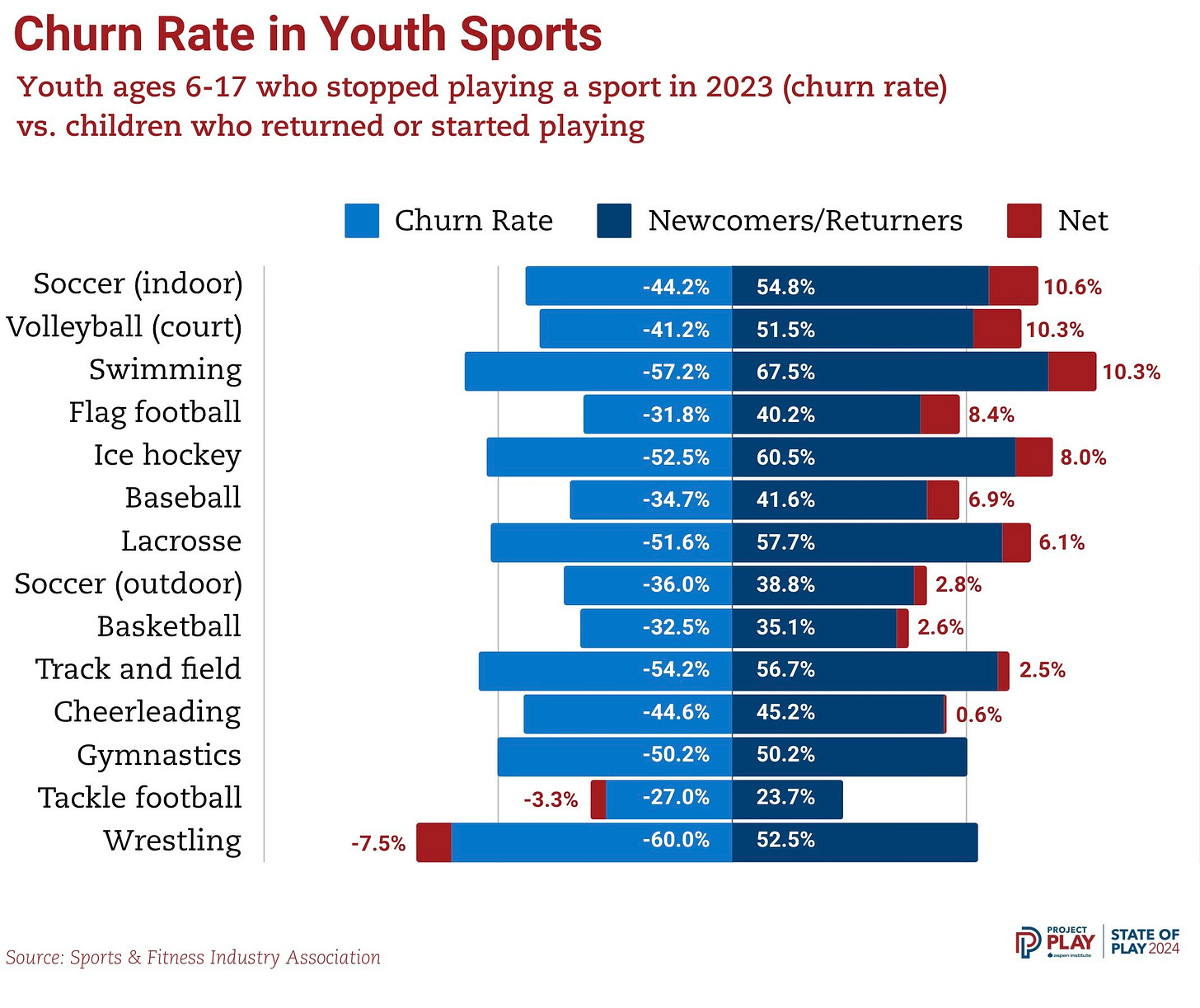

Data also shows that the attrition rate in any given sport is relatively high, with a healthy chunk of players opting out each year and making room for others to jump in. My hunch is that the percentage of kids who have been playing a club sport continuously from age 6 to 17 is close to zero (and if anyone has actual data on this, I’d love to know).

That said, I know from experience that the stakes of opting out of the youth sports arms race are real. And it’s not just that parents are looking for college scholarships; the years of early investment in player development makes it harder for kids to enter these sports in high school, too.

But we could still choose to band together and organize youth sports differently, giving younger kids more free time to play a range of sports before choosing to specialize (if they do at all).

Like the Wait Until 8th movement to delay smart phones, a critical mass of today’s parents could decide to wait until their kids are at least in middle school to specialize in one sport, decreasing the widespread pressure that kids and families feel to invest early on in a club team. And as they do with phones, parents often acknowledge the negative impacts of this culture, but feel powerless to resist it individually.

Parents would have to do so collectively because opting out hinges on giving kids a shared alternative, which leads us back to low stakes settings where they can learn a sport but still have fun. This is what good rec leagues do, but they’ve been slower to come back to life after the pandemic. Club teams with paid coaches generally got back to work pretty quickly after COVID, but it’s been harder to rebuild voluntary leagues led by community volunteers.

I want to believe that some parents and community members would choose to invest in that work. High school players could volunteer as coaches or referees to help kids learn specific skills (and many of them already do). Perhaps the club coaches that are recruiting seven year olds to be “practice players” could instead sponsor small clinics or short-term local seasons that help kids learn the game within the context of a broad invitation to players of all levels. Rebuilding and maintaining rec leagues takes community investment, along with a shared willingness to set aside the goal of creating our own individual athletic superstars in favor of a healthier and more inviting culture for all.

And thankfully there’s something in it for us, too: those rec leagues are close to home, so it means lots less driving.

Have thoughts? Drop a note! I know this is a topic that inspires strong feelings…

I grew up in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, started playing soccer at 5 and played through high school. At this time, there were no club sports. I went to a Catholic school that let everyone be on the team. I started varsity for three years. I was a mediocre player at best, and our team was the worst in the league. I look back on this time with much fondness and am so grateful for this opportunity because I know it doesn’t exist for kids like me today. I have one seven year old son who plays rec soccer (I coach), and we are already seeing the effects of club soccer. My husband and I are older parents with the benefit of observing our friends and relatives parent for the last fifteen plus years. We have decided there will be no club sports in our house for all the reasons stated above. My son will never get a scholarship to play sports. We can invest the money we would have spent on club sports into his college fund (if he chooses to go). However, we will encourage him to try multiple sports at the rec level and to play for as long as he can. We will introduce him to tennis - very low cost - and pay for lessons so we can play as a family. I refuse to participate in the insanity of club sports, and we are consciously opting out of this system.

It occurred to me a few years ago that the most popular activities for kids are all things that can be performed for adults: sports, music, dance, theater. Try finding after school enrichment for the little girl who loves writing stories and poetry, or for the boy who just wants to walk through the woods.

Folks will claim that there’s all sorts of documented benefits to kids’ participation in organized sports, but I think that ignores all the ways they are designed to turn kids into willing middle-class “team players.” The chief beneficiary isn’t children. It’s capitalism.